The Majority Text and the Original Text: Are They Identical?

Related MediaEditor's Note:1

In recent years a small but growing number of New Testament scholars have been promoting what appears to be a return to the Textus Receptus, the Greek text that stands behind the New Testament of the King James Version. But all is not what it appears. In reality, those scholars are advocating “the majority text”—the form of the Greek text found in the majority of extant manuscripts. That the Textus Receptus (TR) resembles the majority text is no accident, since in compiling the TR Erasmus simply used about a half dozen late manuscripts that were available to him. As Hodges points out:

The reason for this resemblance, despite the uncritical way in which the TR was compiled, is easy to explain. It is this: the textual tradition found in Greek manuscripts is for the most part so uniform that to select out of the mass of witnesses almost any manuscript at random is to select a manuscript likely to be very much like most other manuscripts. Thus, when our printed editions were made, the odds favored their early editors coming across manuscripts exhibiting this majority text.2

But the TR is hardly identical with the majority text, for the TR has numerous places where it is supported by few or no Greek manuscripts. Precisely because advocates of the majority text can dissociate themselves from the TR in these places, their argumentation is more sophisticated—and more plausible—than that of TR advocates.

In a previous article3 the present writer interacted with the majority text theory as it has been displayed concretely in The Greek New Testament according to the Majority Text.4 For the most part the interaction was with Zane Hodges’s particular defense of the majority text view. Not all majority text advocates share his approach, however. Indeed, several of the critiques made in that article of Hodges’s “stemmatic reconstruction” are voiced by other majority text advocates. The present article, therefore, is a more general critique of the majority text theory and is specifically intended to interact with Wilbur Pickering’s defense of it.

The present author writes from the perspective of “reasoned eclecticism,” the text critical theory that stands behind almost all modern versions of the New Testament (the New King James Version excepted). Three points in the current debate will be discussed: the theological premise of the majority text theory, the external evidence, and the internal evidence.

Preservation and the Majority Text

For many advocates of the majority text view, a peculiar form of the doctrine of the preservation of Scripture undergirds the entire approach. Their premise is that the doctrine of the preservation of Scripture requires that the early manuscripts cannot point to the original text better than the later manuscripts can, because these early manuscripts are in the minority.

Pickering also seems to embrace such a doctrine. For example in 1968 he argued that this doctrine is “most important” and “what one believes does make a difference.”5 Further he linked the preservation of Scripture to the majority text in such a way that a denial of one necessarily entails a denial of the other: “The doctrine of Divine Preservation of the New Testament Text depends upon the interpretation of the evidence which recognizes the Traditional Text to be the continuation of the autographa.”6 In other words, Pickering seems to be saying, “If we reject the majority text view, we reject the doctrine of preservation.”7

This theological premise has far-reaching implications. For one thing Pickering has charged Hort with being prejudiced against the Byzantine texttype from the very beginning of his research: “It appears Hort did not arrive at his theory through unprejudiced intercourse with the facts. Rather, he deliberately set out to construct a theory that would vindicate his preconceived animosity for the Received Text.”8 But has not Pickering done the same thing? His particular view of preservation seems to have dictated for him that the majority text must be right. In one place he argues:

Presumably the evidence is the same for both believer and unbeliever, but the interpretation of the facts depends upon the presuppositions used. Let the conservative Christian not be ashamed of his presuppositions—they are more reasonable than those of the unbeliever…. God has preserved the text of the New Testament…the Traditional Text is in the fullest sense of the term, just that.9

In other words, according to Pickering, it seems that the Christian’s presupposition is that the majority text is the original text. Apparently to jettison the majority text would be a departure from orthodoxy for many of its advocates. If so, then whatever the merits of this viewpoint are—and there are many—it must be stressed that as long as majority text advocates hold this view of preservation, no amount of evidence will convince them that reasoned eclecticism is right, because the majority text view is “a statement of faith.”10 And as Pickering has so clearly articulated, this is not just a presupposition—it is a doctrine.11

In many respects this theological premise is commendable. Too many evangelicals have abandoned an aspect of the faith when the going got tough. That the majority text proponents have held tenaciously to this doctrinal position—in spite of an ever-increasing mass of evidence—speaks highly of their piety and conviction. But nowhere do they explain why this view of preservation is the biblical doctrine.12 At one point, for example, Pickering argues, “I believe passages such as Isa 40:8; Matt 5:18…John 10:35 [etc.]…can reasonably be taken to imply a promise that the Scriptures will be preserved for man’s use (we are to live ‘by every word of God’).”13 But he gives no further argument, no exegesis. His one clear statement about preservation is this: “God has preserved the text of the New Testament in a very pure form and it has been readily available to His followers in every age throughout 1900 years.”14 No proof text is given, just a bare statement.15

The present writer has several serious problems with this view of the doctrine of preservation, three of which are as follows.16 First, Scripture does not state how God has preserved the text. It could be in the majority of witnesses, or it could be in a small handful of witnesses. In fact theologically one may wish to argue against the majority: usually it is the remnant, not the majority, that is right.17

Second, assuming that the majority text is the original, then this pure form of text has become available only since 1982.18 The Textus Receptus differs from it in almost 2,000 places—and in fact has several readings that have “never been found in any known Greek manuscript,” and scores, perhaps hundreds, of readings that depend on only a handful of very late manuscripts.19 Many of these passages are theologically significant texts.20 Yet virtually no one had access to any other text from 1516 to 1881, a period of over 350 years. In light of this it is difficult to understand what Pickering means when he says that this pure text “has been readily available to [God’s] followers in every age throughout 1900 years.”21 Purity, it seems, has to be a relative term.

Third, again assuming that the majority text is the original and that it has been readily available to Christians for 1,900 years, then it must have been readily available to Christians in Egypt in the first four centuries. But this is demonstrably not true. Literally scores of studies in the last 80 years have demonstrated this point.22 Due to space considerations only one recent doctoral dissertation will be cited. After carefully investigating the Gospel quotations of Didymus, a fourth-century Egyptian writer, Ehrman concludes, “These findings indicate that no ‘proto-Byzantine’ text existed in Alexandria in Didymus’ day or, at least if it did, it made no impact on the mainstream of the textual tradition there.”23 Pickering speaks of the early Alexandrian witnesses as “polluted” and as coming from a “sewer pipe.”24 Now if these manuscripts are really that defective, and if this is all Egypt had in the first three or four centuries, then this peculiar doctrine of preservation is in serious jeopardy, for those ancient Egyptian Christians had no access to the pure stream of the majority text. If one defines preservation in terms of the majority text, one ends with a view that speaks poorly of God’s sovereign care of the text in ancient Egypt.

In reality, to argue for the purity of the Byzantine stream, as opposed to the pollution introduced by the Alexandrian manuscripts, is to blow out of proportion what the differences between these two texts really are—both in quantity and quality. For over 250 years, New Testament scholars have argued that no textual variant affects any doctrine. Carson has gone so far as to state that “nothing we believe to be doctrinally true, and nothing we are commanded to do, is in any way jeopardized by the variants. This is true for any textual tradition. The interpretation of individual passages may well be called in question; but never is a doctrine affected.”25 The remarkable thing is that this applies both to the standard critical texts of the Greek New Testament and to Hodges’s and Farstad’s Majority Text; doctrine is not affected by the variants between them.26

If the quality of the text (i.e., its doctrinal purity) is not at stake, then what about the quantity? How different is the Majority Text from the United Bible Societies’ Greek New Testament or the Nestle-Aland text? Do they agree only 30 percent of the time? Do they agree perhaps as much as 50 percent of the time? This can be measured, in a general sort of way. There are approximately 300,000 textual variants among New Testament manuscripts. The Majority Text differs from the Textus Receptus in almost 2,000 places. So the agreement is better than 99 percent. But the Majority Text differs from the modern critical text in only about 6,500 places. In other words the two texts agree almost 98 percent of the time.27 Not only that, but the vast majority of these differences are so minor that they neither show up in translation nor affect exegesis. Consequently the majority text and modern critical texts are very much alike, in both quality and quantity.

To sum up: as long as the doctrine of preservation and the majority text view are inseparably linked, it seems that no amount of evidence can overcome the majority text theory.28 But if the doctrine of preservation is not at stake, then evangelical students and pastors are free to examine the evidence without fear of defection from orthodoxy.29

External Evidence

The primary premise in the majority text view is this: “Any reading overwhelmingly attested by the manuscript tradition is more likely to be original than its rival(s).”30 In other words when the majority of manuscripts agree, that is the original.31 Majority text advocates have turned this presumption into a statistical probability.32 But in historical investigation, statistical probability is almost always worthless. David Hume, in his Essay on Miracles, argued against miracles on the basis of statistical probability. The majority of people Hume had ever known had never been raised from the dead. In fact none of them had. But belief in the resurrection of Christ is not based on statistical probability—there is evidence which, in this case, overturns statistics.

In historical investigation, presumption is only presumption. An ounce of evidence is worth a pound of presumption. The story has been told that in Aristotle’s day Greek philosophers had developed intricate theories as to what constituted the innards of a frog. In fact there was a great deal of consensus on this—one might even say a “majority view.” But it was all presumption—and it was all overturned as soon as someone cut open a frog and looked at the evidence.

In textual criticism there are three categories of external evidence: the Greek manuscripts, the early translations into other languages, and the quotations of the New Testament found in the church fathers’ writings. If the majority text view is right, then one would expect to find this text form (often known as the Byzantine text) in the earliest Greek manuscripts, in the earliest versions, and in the earliest church fathers. Not only would one expect to find it there, but also one would expect it to be in a majority of manuscripts, versions, and fathers.

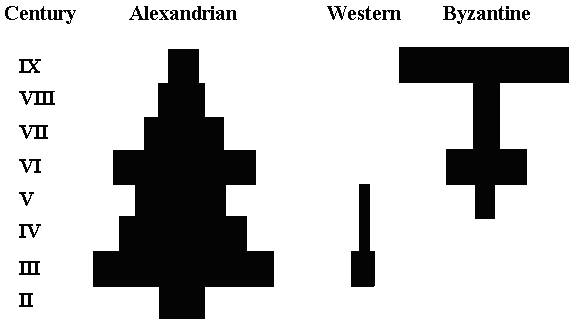

But that is not what is found. Among extant Greek manuscripts, what is today the majority text did not become a majority until the ninth century. In fact, as far as the extant witnesses reveal, the majority text did not exist in the first four centuries. Not only this, but for the letters of Paul, not even one majority text manuscript exists from before the ninth century. To embrace the majority text for the Pauline Epistles, then, requires an 800-year leap of faith.

When Westcott and Hort developed their theory of textual criticism, only one papyrus manuscript was known to them. Since that time almost 100 have been discovered. More than fifty of these came from before the middle of the fourth century. Yet not one belongs to the majority text. The Westcott-Hort theory, with its many flaws (which all textual critics today acknowledge), was apparently still right on its basic tenet: the Byzantine texttype—or majority text—did not exist in the first three centuries. The evidence can be visualized as follows, with the width of the horizontal bars indicating the relative number of extant manuscripts from each century.

Many hypotheses can be put forth as to why there are no early Byzantine manuscripts. But once again an ounce of evidence is worth a pound of presumption. In historical investigation one must start with the evidence and then make the hypothesis.

This chart does not tell the whole story. The extant Greek manuscripts—the primary witnesses to the text of the New Testament—do not include the Byzantine text in the first four centuries. But what about the early versions and the church fathers? Do they attest to the Byzantine texttype in the early period?

Many of the versions were translated from Greek at an early date. Most scholars believe that the New Testament was translated into Latin in the second century A.D.33—two centuries before Jerome produced the Vulgate. Almost one hundred extant Latin manuscripts represent this Old Latin translation—and they all attest to the Western texttype. In other words the Greek manuscripts they translated were not Byzantine. The Coptic version also goes back to an early date, probably the second century34—and it was a translation of Alexandrian manuscripts, not Byzantine ones. The earliest forms of the Syriac are also either Western or Alexandrian.35 What is the oldest version, then, that is based on the majority text? In a carefully documented study, Metzger points out that the Gothic version is “the oldest representative of the…Antiochian [i.e., Byzantine] type of text.”36 When was this version produced? At the end of the fourth century.

The significance of these early versions is twofold:37 (1) None of the versions produced in the first three centuries was based on the Byzantine text. But if the majority text view is right, then each one of these versions was based on polluted Greek manuscripts—a suggestion that does not augur well for God’s providential care of the New Testament text, as that care is understood by the majority text view.38 But if these versions were based on polluted manuscripts, one would expect them to have come from (and be used in) only one isolated region. This is not the case; the Coptic, Ethiopic, Latin, and Syriac versions came from all over the Mediterranean region. In none of these locales was the Byzantine text apparently used. This is strong evidence that the Byzantine text simply did not exist in the first three centuries—anywhere.39 (2) Even if one of these early versions had been based on the majority text, this would only prove that the majority text existed before the fourth century. But it would not prove that it was in the majority before the fourth century.40

Early patristic writers are especially valuable in textual criticism because it can be determined when and where they lived. Many of them lived much earlier than the date of any Greek manuscripts now extant for a particular book. Some lived in the first or early second century. If it could be determined what kind of text they used when they quoted from the New Testament, such information would naturally be highly valuable. But textual critics do not usually give much weight to the church fathers. There are several reasons for this, some of which are as follows. First, when a church father quotes from the New Testament, it is not always possible to tell if he is quoting from memory or if he has a manuscript in front of him. Second, he rarely tells which book he is quoting from. He might say, “as it is written,” or “just as Paul says,” or “our Lord said.” Third, none of the original documents of any church fathers remains. Almost all the copies of these early patristic writers come from the Middle Ages. In other words textual criticism must be done on the church fathers in order to see how they attest to the New Testament text.

This last problem is significant because the Byzantine text was the majority text after the ninth century. And virtually all the copies of the fathers come from the ninth century or later. When a scribe was copying the New Testament text quoted by a church father, he would naturally conform that text to the one with which he was familiar.41 This fact has been recognized for the past 80 years. In 1912, Frederic G. Kenyon, a British textual critic, wrote, “Without any prejudice against the received text [i.e., the Byzantine text], it must be recognized that, where two alternatives are open, the one which diverges from the received text is more likely to be the one originally used by the Father in question.”42

This introduction to patristic use of Scripture is necessary to underscore the following two points. (1) Older studies, which were based on late copies of the church fathers and on uncritical editions, are not helpful in determining what the church fathers said. And it is precisely these older studies that the majority text advocates appeal to.43 (2) So far as this writer is aware, in the last 80 years every critical study has concluded that the majority text was never the text used by the church fathers in the first three centuries. Fee, who is recognized as one of the leading patristic authorities today, wrote:

Over the past eight years I have been collecting the Greek patristic evidence for Luke and John for the International Greek New Testament Project. In all of this material I have found one invariable: a good critical edition of a father’s text, or the discovery of early MSS, always moves the father’s text of the NT away from the TR and closer to the text of our modern critical editions.44

In other words when a critical study is made of a church father’s text or when early copies of a church father’s writings are discovered, the majority text is found wanting. The early fathers had a text that keeps looking more like modern critical editions and less like the majority text.45

In summing up the evidence from the early church fathers, in none of the critical studies made in the last 80 years was the majority text found to be the text used by the church fathers in the first three centuries.46 Though some of these early Fathers had isolated Byzantine readings, the earliest church father to use the Byzantine text was the heretic Asterius, a fourth-century writer.47

All the external evidence suggests that there is no proof that the Byzantine text was in existence in the first three centuries. It is not found in the extant Greek manuscripts, nor in the early versions, nor in the early church fathers. And this is a threefold cord not easily broken. To be sure, isolated Byzantine readings have been found, but not the Byzantine texttype. Though some Byzantine readings existed early, the texttype apparently did not.48

Another comment is in order regarding external evidence. On several occasions church fathers do more than quote the text. They also discuss textual variants. Holmes points out the value of this for the present discussion.

Final proof that the manuscripts known today do not accurately represent the state of affairs in earlier centuries comes from patristic references to variants once widely known but found today in only a few or even no witnesses. The “longer ending” of Mark, 16:9–20 {Mark 16}, today is found in a large majority of Greek manuscripts; yet according to Jerome, it “is met with in only a few copies of the Gospel—almost all the codices of Greece being without this passage.” Similarly, at Matthew 5:22 he notes that “most of the ancient copies” do not contain the qualification “without cause”…which, however, is found in the great majority today.49

Metzger discusses several references in Jerome, Origen, and other early writers where a variant found in the majority of manuscripts in their day is now found in a minority of manuscripts, as well as the other way around.50 “In other words, variants once apparently in the minority are today dominant, and vice versa; some once dominant have even disappeared. This fact alone rules out any attempt to settle textual questions by statistical means.”51

Internal Evidence

Most textual critics are persuaded that the external evidence of the first three centuries is conclusive against the majority text. But it would be a gross misrepresentation of the facts to say that all these witnesses of the early period agree with each other all the time. It is well recognized that the Byzantine manuscripts—from the ninth or tenth century on at least—are far more uniform than the early Alexandrian or Western manuscripts. Several factors account for this, but it is ancillary to the present discussion. The question at the moment is this: When the earliest manuscripts disagree with one another, how should the text critic decide which ones are right?

This is where internal evidence enters the picture. Internal evidence has to do with determining which variant is original on the basis of known scribal habits and the author’s style. The aim is to choose the reading that best explains the rise of the others.

At first this process may sound subjective. Yet people do it every day—every time they read a newspaper. For example if someone were to look at the Win-Loss column for the Los Angeles Lakers and see 38 losses and only 12 wins, he would know that the typesetter switched the numbers. If he saw an article by Harold Hoehner in which A.D. 30 was mentioned as the crucifixion date, the reader could be sure that this was a printing mistake. Not all internal evidence is subjective, then—or else proofreaders would have no jobs.

The central element in the procedures used by Westcott and Hort …was the internal evidence of documents. Their high appraisal of the [Alexandrian] tradition in preference to “Western” or Byzantine readings rests essentially on internal evidence of readings…it is upon this basis that most contemporary critics, even while rejecting [Westcott and Hort’s] historical reconstructions, continue to follow them in viewing the Majority text as secondary.52

In other words Westcott and Hort—without the knowledge of the early papyri discovered since their time—felt that the majority text was inferior because of internal evidence. (The papyri have simply confirmed their views.) “Majority text advocates, however, object quite strenuously to the use of the canons of internal evidence. These canons, they argue, are only very broad generalizations about scribal tendencies which are sometimes wrong and in any case frequently cancel each other out.”53

There is some truth to this point; in fact even Fee, an ardent opponent of the majority text, has argued likewise. But the fact that internal evidence can be subjective does not mean that it is all equally subjective. “Reasoned eclecticism” maintains today that several canons of internal evidence are “objectively verifiable,”54 or virtually so. And where they are, the majority text (as well as the Western text) almost always has an inferior reading, while the Alexandrian manuscripts almost always have a superior reading.55

One may consult, for example, Metzger’s A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament to see some of the rationale for accepting one reading over another. Some of the internal criteria are quite subjective—but not all are. One should note especially the places in which Metzger defends the ‘A’ rating of the UBS text.56

One other comment is needed here. It seems that the majority text advocates appeal so much to external evidence because they want certainty about the original wording in every place.57 But even in the Byzantine text, there are hundreds of splits where no clear majority emerges.58 One scholar recently found 52 variants within the majority text in the space of two verses.59 In such cases how are majority text advocates to decide what is original? If internal evidence is totally subjective, then in those places the majority text view has no solution, and no certainty. Perhaps this is why Pickering recently said, “Not only are we presently unable to specify the precise wording of the original text, but it will require considerable time and effort before we can be in a position to do so.”60

To sum up, though internal evidence is subjective, it is not all equally subjective. And it is precisely where internal evidence is “objectively verifiable” (or virtually so) that most scholars today maintain that the majority text contains a secondary reading. Furthermore in the quest for certainty the majority text theory is in many respects worse off than reasoned eclecticism.61

Once again the reader should be reminded of a point made earlier. Though textual criticism cannot yet produce certainty about the exact wording of the original, this uncertainty affects only about two percent of the text. And in that two percent support always exists for what the original said—never is one left with mere conjecture. In other words it is not that only 90 percent of the original text exists in the extant Greek manuscripts—rather, 110 percent exists. Textual criticism is not involved in reinventing the original; it is involved in discarding the spurious, in burning the dross to get to the gold.

Conclusion

Is the majority text identical with the original text? The present writer does not think so. There are no doctrinal reasons that compel him to believe that it is, and when all the evidence is weighed—both external and internal—it is quite compelling against such a view. Does this mean that the majority text is worthless? Not at all. For one thing, it agrees with the critical text 98 percent of the time. For another, several isolated Byzantine readings are early, and where they have good internal credentials, reasoned eclectics adopt them as original. But this is not, by any stretch of the imagination, a wholesale adoption of the majority text. And that is precisely the issue taken up in this article.

1 On February 21, 1990, Wilbur N. Pickering, president of the Majority Text Society, gave a lecture at Dallas Theological Seminary on the majority text and the original text. He took the position that the two were virtually identical. On February 23 the present writer responded. This article is an adaptation of that response.

2 Zane C. Hodges, “A Defense of the Majority-Text” (Dallas: Dallas Seminary Book Room, n.d.), p. 1.

3 Daniel B. Wallace, “Some Second Thoughts on the Majority Text,” Bibliotheca Sacra 146 (July–September 1989): 270–90.

4 Edited by Zane C. Hodges and Arthur L. Farstad (Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 1982).

5 Wilbur N. Pickering, “An Evaluation of the Contribution of John William Burgon to New Testament Textual Criticism” (ThM thesis, Dallas Theological Seminary, 1968), p. 86.

6 Ibid., p. 91.

7 More recently, Pickering has linked inspiration and preservation so closely that he argued that a denial of one was the denial of the other: “Are we to say that God was unable to protect the text of Mark or that He just couldn’t be bothered? I see no other alternative—either He didn’t care or He was helpless. And either option is fatal to the claim that Mark’s Gospel is ‘God-breathed’“ (“Mark 16:9–20 and the Doctrine of Inspiration” [unpublished paper distributed to members of the Majority Text Society, September 1988], p. 1).

8 Wilbur N. Pickering, The Identity of the New Testament Text, 2d ed. (Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 1980), p. 32. No one today would deny that this was Hort’s starting point. Indeed, modern textual critics have recognized that Hort depended entirely too much on Aleph and B—so much so that the UBS edition has adopted scores of readings that are attested by the Byzantine texttype (and other witnesses) against these two codices. Precisely because modern textual critics do not share the same rigid presupposition that Hort embraced, they are able to see the value of readings not found in these two uncial texts. In this respect majority text advocates’ presuppositions govern their methods far more drastically than do reasoned eclectics’ presuppositions. In fact majority text advocates often see the issue as so black and white that if even one majority text reading were proved false, their whole theory would collapse. Hort held the opposite (no distinctive Byzantine reading is original), and majority text advocates continue to write in a triumphant manner when they can prove Hort wrong on this point, usually assuming that reasoned eclecticism is thereby falsified.

9 Pickering, “An Evaluation of the Contribution of John William Burgon to New Testament Textual Criticism,” p. 90. First italics added; second, Pickering’s.

10 Pickering, The Identity of the New Testament Text, p. 154.

11 It is noteworthy that Pickering has changed his wording between his master’s thesis and The Identity of the New Testament Text. What is called “the doctrine of Preservation” in his thesis has become, at most, a “presupposition” in Identity. This euphemistic alteration masks what the real issue is: to deny the majority text is to embrace heresy. In one place he even states, “In the author’s opinion, those conservative schools and scholars who have propagated Hort’s theory and text (Nestle is essentially Hortian) bear a heavy responsibility for the growing doubt and disbelief throughout the Church. The ‘neo-evangelical’ defection on Scriptural inerrancy is a case in point” (“An Evaluation of the Contribution of John William Burgon to New Testament Textual Criticism,” p. 90). In this sweeping statement, he has condemned B. B. Warfield and D. A. Carson, the vast bulk of scholars in the Evangelical Theological Society (whose doctrinal statement strongly affirms inerrancy), and almost all the faculty of Dallas Seminary—not to mention the first reader of his own thesis, S. Lewis Johnson, Jr.

12 In 1980 Pickering argued that “any thoughtful person will realize that it is impossible to work without presuppositions—but a serious effort should be made to let the evidence tell its own story. It is not legitimate to declare a priori what the situation must be, on the basis of one’s presuppositions” (The Identity of the New Testament Text, p. 153). But his thesis, which unashamedly declared this doctrinal position, preceded the book by 12 years.

13 Ibid., p. 153 (italics his).

14 Pickering, “An Evaluation of the Contribution of John William Burgon to New Testament Textual Criticism,” p. 90.

15 Although Pickering provides no proof text for his view of preservation, he views it as the logical corollary to inspiration: “If the Scriptures have not been preserved then the doctrine of Inspiration is a purely academic matter with no relevance for us today. If we do not have the inspired Words or do not know precisely which they be, then the doctrine of Inspiration is inapplicable” (ibid., p. 88). Elsewhere he argues that uncertainty over the text not only makes inspiration inapplicable, but also untrue (“Mark 16:9–20 and the Doctrine of Inspiration,” p. 1). There are several fallacies in this thinking, both on a historical level and on a logical one. Historically only since 1982 has The Greek New Testament according to the Majority Text (hereafter referred to as the Majority Text) been available. Consequently, assuming that it is an exact reproduction of the autographs, for almost 2,000 years the doctrine of inspiration was inapplicable. Logically three observations may be made: (a) The equation of inspiration with man’s recognition of what is inspired (in all its particulars) virtually puts God at the mercy of man and requires omniscience of man. The burden is so great that a text critical method of merely counting noses seems to be the only way in which man can be “relatively omniscient.” In what other area of Christian teaching is man’s recognition required for a doctrine to be true? (b) The argument that reasoned eclecticism does “not have the inspired Words” implies that textual critics must constantly resort to conjectural emendation—i.e., to reinvent the original from thin air as it were. But this is not a valid charge. Reasoned eclectics simply do not resort to conjectural emendation—there is textual basis for the readings they select. Consequently, it is certain that the original wording is found either in the text or in the apparatus. (c) Even majority text advocates “do not know precisely” which words are original in every place, as Pickering himself admits (The Identity of the New Testament Text, p. 150). Actually this kind of argument is more befitting defenders of the Textus Receptus. Since it backfires for majority text advocates, it has no place in the discussion.

16 For an excellent critique, see Bart D. Ehrman, “New Testament Textual Criticism: Quest for Methodology” (MDiv thesis, Princeton Theological Seminary, 1981), pp. 140–52. In addition any view of preservation must be the same for both testaments, else one is subject to the charge of Marcionism. But virtually all Old Testament textual critics—even those who embrace inerrancy—recognize the need, albeit rare, for conjectural emendation (and significantly some of the conjectures of an earlier generation have now found support in the earliest witnesses to the Hebrew text found in Qumran). This hardly comports with a “majority text” theory.

17 Harold W. Hoehner suggested this argument and analogy (personal interview).

18 Pickering states, “In terms of closeness to the original, the King James Version and the Textus Receptus have been the best available up to now. In 1982 Thomas Nelson Publishers brought out a critical edition of the Traditional Text (Majority, ‘Byzantine’) under the editorship of Zane C. Hodges, Arthur L. Farstad, and others which while not definitive will prove to be very close to the final product, I believe. In it we have an excellent interim Greek Text to use until the full and final story can be told” (The Identity of the New Testament, p. 150).

19 Bruce M. Metzger, The Text of the New Testament, 2d ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1968), p. 100.

20 E.g., 1 John 5:7–8 and Revelation 22:19.

21 Pickering was unaware there would be so many differences between the Textus Receptus and Majority Text when he wrote this note. Originally his estimate was between 500 and 1,000 differences (“An Evaluation of the Contribution of John William Burgon to New Testament Textual Criticism,” p. 120). But in light of the 2,000 differences, “purity” becomes such an elastic term that it is removed from being a doctrinal consideration.

22 Pickering has not evidenced awareness of these. Gordon Fee speaks of Pickering’s “neglect of literally scores of scholarly studies that contravene his assertions,” and states, “The overlooked bibliography here is so large that it can hardly be given in a footnote. For example, I know eleven different studies on Origen alone that contradict all of Pickering’s discussion, and not one of them is even recognized to have existed” (“A Critique of W. N. Pickering’s The Identity of the New Testament Text: A Review Article,” Westminster Theological Journal 41 [1978–79]: 415).

23 Bart D. Ehrman, Didymus the Blind and the Text of the Gospels (Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1986), p. 260 (italics added). What confirms this further is that in several places Origen, the great Christian textual scholar, speaks of textual variants that were in a majority of manuscripts in his day, yet today are in a minority, and vice versa. Granting every gratuitous concession to majority text advocates, in the least this shows that no majority text was “readily available” to Christians in Egypt.

24 Pickering, “An Evaluation of the Contribution of John William Burgon to New Testament Textual Criticism,” p. 93.

25 D. A. Carson, The King James Version Debate: A Plea for Realism (Grand Rapids: Baker Book House, 1979), p. 56. The present writer thinks that Carson has perhaps mildly overstated the case. He would rather state it more cautiously: “No viable variant affects any major doctrine.” But it is readily admitted that he is virtually alone in this; no other textual critic, so far as he knows, couches his terms so tentatively. One other point should be mentioned here: Carson’s statement that Christian doctrines are not jeopardized by textual variants is based on the manuscript evidence, not on the doctrine of preservation. Here is a good instance in which the evidence dictates the shape of the proposition, not vice versa.

26 Sometimes it is alleged that there is no ascension of Christ in the Western texts (e.g., Theo. P. Letis, “In Reply to D. A. Carson’s ‘The King James Version Debate,’“ in The Majority Text: Essays and Reviews in the Continuing Debate, ed. Theo. P. Letis [Fort Wayne, IN: Institute for Biblical Textual Studies, 1987], pp. 199–200). That is not true. Although a portion of the Western text does omit the ascension in Luke 24:51, it retains it in Acts 1:11 (a few Western witnesses omit the second “into heaven” [εἰς τὸν οὐρανόν], but not the third “into heaven”). (These Western witnesses are not followed by the editors of the UBS text.) Further, this doctrine is implicit throughout Hebrews and explicit in 1 Peter 3:21–22. It must be stressed that though occasionally a particular doctrinal proof text is altered or deleted among the manuscripts, never is such a doctrine omitted altogether. Further, the charge cuts both ways. The fact that the Majority Text alters the Comma Johanneum (1 John 5:7–8) (against the Textus Receptus) means that it has deleted the strongest proof text of the Trinity from the New Testament. (Nevertheless the orthodox affirmation of the Trinity in no way depends on the Comma Johanneum.)

27 Actually this number is a bit high, because there can be several variants for one particular textual problem, but only one of these could show up in a rival printed text. Nevertheless the point is not disturbed. If the percentages for the critical text are lowered, those for the Textus Receptus must also be correspondingly lowered.

28 Zane Hodges is much more cautious in how he weds preservation and majority text (but see Ehrman, “New Testament Textual Criticism: Quest for Methodology,” pp. 140–52). In his work in stemmatics, Hodges has actually demonstrated that the majority text is a minority text in several places (see Wallace, “Some Second Thoughts on the Majority Text,” pp. 270–90). Predictably, because preservation is more fundamental to Pickering’s view, he thinks that Hodges is wrong in adopting minority text readings.

29 Ironically Pickering does not realize that he is looking in a mirror when he writes: “Throughout the paper heavy use has been made of the writings of men like Aland, Colwell, and Zuntz who seem to come close to Burgon’s opinion on quite a number of details within the total field. Yet, it is obvious that these men do not buy Burgon’s basic position or method. Why? Possibly they are having difficulty in getting free from the presuppositions instilled in them during their student days. They seem to be reacting to the evidence consistently at different isolated points but seem to be unable to break away from the Hort framework. There may be a subconscious theological necessity not to reconsider the status of the ‘Byzantine’ text” seriously (“An Evaluation of the Contribution of John William Burgon to New Testament Textual Criticism,” p. 110). The charge of “theological necessity” would seem to apply more to Pickering than to the men he cites.

30 The Greek New Testament according to the Majority Text, p. xi. Hodges and Farstad give a second principle: “(2) Final decisions about readings ought to be made on the basis of a reconstruction of their history in the manuscript tradition” (p. xii). Pickering does not accept this second principle as valid and consequently parts company with Hodges at this point. For a critique of the stemmatic reconstruction principle, see Daniel B. Wallace, “Some Second Thoughts on the Majority Text,” pp. 282–85.

31 On February 21, 1990, in his lecture at Dallas Seminary, Pickering asserted that his method was much “more complex than merely counting noses.” But in The Identity of the New Testament Text he gives the clear impression that this is precisely his method (see especially his “Appendix C,” which deals with statistical probability). It seems that he has confused method with rationale for the method. The rationale may be somewhat complex, but the method is quite simple: count “noses.”

32 The Identity of the New Testament Text, “Appendix C: The Implications of Statistical Probability for the History of the Text,” pp. 159–69.

33 See Bruce M. Metzger’s helpful discussion in The Early Versions of the New Testament: Their Origin, Transmission and Limitations (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1977), pp. 285–93.

34 Ibid., pp. 125–33.

35 Majority text advocates appeal to the Syriac Peshitta as both coming from the second century and being a translation of the Byzantine text. However, although recent scholarship has recognized that the Peshitta must have originated before A.D. 431, it has also concluded that (1) it was not the earliest form of the text in Syriac, probably finding its origins in the fourth to late fourth century; and (2) its textual affinities are not altogether clear (see ibid., pp. 56–63).

36 Ibid., p. 385. He adds, “At the same time not a few Western readings are embedded in this Antiochian base, many of which agree with Old Latin witnesses.”

37 Three other points can be mentioned. First, majority text advocates are fond of saying that since the roots of the majority text are shrouded in mystery, it must not have come from a deliberate recension. They argue this way on the analogy of one version, the Latin Vulgate (for it is known historically that Jerome produced this). But the Vulgate is the exception rather than the rule. Metzger points out, for example: “The exact date of the first Latin version of the Bible, or indeed of any part of the Bible, is uncertain. It is a remarkable fact that the Latin churches do not seem to have retained any memory of this great event in their history. Latin patristic writers report no legend or tradition bearing on the subject” (ibid., p. 286). The unknown roots of a particular tradition, consequently, do not compel one to argue that it goes back to the original.

Second, the extant versional manuscripts are virtually triple the extant Greek manuscripts in number (i.e., there are about 15,000 versional manuscripts). The vast majority of them (mostly 10,000 Vulgate copies) do not affirm the Byzantine text. If one wishes to speak about the majority, why restrict the discussion only to extant Greek witnesses and not include the versional witnesses?

Third, regarding Pickering’s appeal to preservation: to argue that the pure text has been readily available to Christians for 1,900 years must refer only to Christians who knew Greek. Yet this was only a small corner of the world after the fourth century. The fact that the Latin Vulgate looks more like the Alexandrian text than the Byzantine text means that Christians in the West never had ready access to the so-called pure text. That the Vulgate is a version is not irrelevant; Pickering’s point about preservation is related to usage, as he shows in his italicized quotation of Matthew 4:4. And if it is related to usage, then it cannot be restricted to Greek.

38 Incidentally, in his discussion of 1 Timothy 3:16 Pickering suggests that the earliest Syriac, Coptic, and Latin versions adopted a reading (“which”) that was based on a corrupt reading (“who”) of the original text (“God”) (“The Majority Text and the Original Text: A Response to Gordon D. Fee,” in The Majority Text: Essays and Reviews in the Continuing Debate, p. 39). Not only does he not explain how a corruption of a corruption could have crept in so quickly, but he apparently does not recognize that to call these versions corrupt at this point is to deny his own view of the doctrine of preservation.

39 The versions also clarify the situation in another way. Metzger refers to “Origen and Jerome, whose sustained critical labors on the text of the Bible are among the most outstanding of any age” (Bruce M. Metzger, “The Practice of Textual Criticism among the Church Fathers,” in New Testament Studies: Philological, Versional, and Patristic [Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1980], p. 189). Further, Metzger argues, “Among the more scholarly patristic writers Origen and Jerome take first place in the Eastern and the Western Churches respectively” (“St. Jerome’s Explicit References to Variant Readings in Manuscripts of the New Testament,” ibid., p. 199). It is well known that Origen used an Alexandrian text. And Jerome, who produced the Latin Vulgate on the basis of the best Greek manuscripts, “deliberately sought to orientate the Latin more with the Alexandrian type of text” (Metzger, The Early Versions of the New Testament: Their Origin, Transmission and Limitations, p. 359).

40 This point is significant because majority text advocates labor strenuously to prove merely the early existence of the Byzantine text, while tacitly assuming that this would also prove numerical superiority in the early centuries.

41 Though some majority text advocates may wish to deny that scribes did this, such a denial destroys another argument used by majority text advocates. Often they rely on Arthur Vööbus’s work on the text of Rabbula of Edessa to dismantle F. C. Burkitt’s notion that Rabbula was the originator of the Syriac Peshitta. But in doing so, majority text proponents make the evidence say more than it really does. They argue that since Rabbula did not originate the Peshitta (a point Metzger regards as “proved” by Vööbus, and virtually all textual critics now agree), it must go back early, perhaps as early as the second century. (For rebuttal of so early a date, see ibid., pp. 56–63.)

How does this relate to scribal changes of patristic New Testament quotations? It has to do with Vööbus’s method in proving that the Peshitta does not originate with Rabbula: “In default of the existence of any extensive composition by Rabbula himself, Vööbus analyzed the New Testament quotations in Rabbula’s Syriac translation of Cyril of Alexandria’s Περὶ τῆς ὀρθῆς πίστεως, written shortly after the beginning of the Nestorian controversy in 430. In this translation, instead of rendering Cyril’s quotations from Scripture, Rabbula inserted the wording of the current Syriac version—a method which more than one author followed in translating from Greek into Syriac” (ibid., p. 58). Majority text advocates must recognize this insertion of a version in currency only at a later date, rather than that of the ancient writer. Otherwise one of their strongest pillars (the supposed early date of the Peshitta) falls to the ground. And once they concede this, another pillar (that early fathers must have used the majority text, since later copies of their works did) cannot bear the weight they give it.

42 Frederic G. Kenyon, Handbook to the Textual Criticism of the New Testament, 2d ed. (New York: Macmillan Co., 1912), p. 244. Pickering protests to this approach, calling it “‘rigged’ against the TR.” He states, “The generalization is based on the presupposition that the ‘Byzantine’ text is late—but this is the very point to be proved and may not be assumed” (The Identity of the New Testament Text, p. 73). Actually, as Kenyon points out, there is no prejudice against the majority text here. The premise is not that the Byzantine text is late, but that it was in the majority when the church fathers were copied. Surely majority text advocates agree to that. Further, if one assumes careful copying by Byzantine scribes (as majority text advocates do), then an alteration of a church father’s text away from the majority text could not be due to carelessness. Finally, as Fee points out, it is not merely a good, critical copy of a church father’s text that moves it away from the Byzantine texttype; every early copy does the same thing (see note 44). Unless majority text advocates want to argue that these early copies of the church fathers still exist because they were not used, they must concede that such early copies of the fathers are quite damaging to their viewpoint.

43 Remarkably, Pickering has most recently argued on both sides of the issue. In his rebuttal of Kurt Aland’s “The Text of the Church?” (Trinity Journal 8 [1987]: 131–44), where Aland gives substantial evidence that the early fathers did not use the majority text, Pickering says, “Something that Aland does not explain, but that absolutely demands attention, is the extent to which these early Fathers apparently cited neither the Egyptian nor the Majority texts—about half the time. Should this be interpreted as evidence against the authenticity of both the Majority and Egyptian texts? Probably not, and for the following reason: a careful distinction must be made between citation, quotation and transcription…. All Patristic ‘citation’ needs to be evaluated with this distinction in mind and must not be pushed beyond its limits. In any case, Aland’s objectivity is suspect—all his statements of evidence need to be verified by someone with a different bias” (“The Text of the Church” [unpublished paper distributed to members of the Majority Text Society, November 1989], p. 4).

In other words Pickering appeals to at least a modicum of critical reconstruction of a church father’s words. But then in the following paragraph he argues, “John W. Burgon made copious reference to Patristic citations in all his works; his massive index of 86,489 such citations is still the most extensive in existence (so far as I know)” (ibid.). This comment was in response to Aland’s point that majority text protagonists “completely overlook the quotations from the New Testament found in the writings of the church fathers” (Aland, “The Text of the Church,” p. 139). Pickering is appealing to an uncritical text of the fathers, using late manuscripts, as a basis for the suggestion that the Byzantine texttype is early—and right after he criticized Aland for not making a critical study of the Fathers’ texts.

44 Gordon D. Fee, “Modern Textual Criticism and the Revival of the Textus Receptus,” Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society 21 (1978): 26.

45 For example, concerning Origen’s commentary on John, Fee says that “in citations where we have the highest level of certainty, Origen’s text is 100 per cent Egyptian” (“Origen’s Text of the New Testament and the Text of Egypt,” New Testament Studies 28 [1982]: 355).

46 A few comments should be made here about Aland’s recent study in Trinity Journal, since that study seems to counter this statement (cf. note 43). First, it is not critical, as even Pickering points out (“The Text of the Church,” p. 4).

Second, even with all the allowances made in the direction of the majority text, i.e., combining percentages of readings which (a) support the majority text against the Alexandrian text and those which (b) support the majority text as well as the Alexandrian text, one finds that:

Marcion (c. 160?) supported MT 28% of the time (18% against the Alexandrian);

Irenaeus (d. 202) supported MT 33% (16.5% against Alexandrian);

Clement of Alexandria (d. 215) supported MT 44% (15% against Alexandrian);

Origen (d. 254) supported MT 45% (17% against Alexandrian);

Hippolytus (d. 235) supported MT 50% (19% against Alexandrian);

Methodius (280?) supported MT 50% (19% against Alexandrian);

Adamantius (d. 300) supported MT 52% (31% against Alexandrian);

Asterius (d. 341) supported MT 90% (50% against Alexandrian);

Basil (d. 379) supported MT 79% (40% against Alexandrian);

Apostolic Constitutions (380?) supported MT 74% (41% against Alexandrian);

Epiphanius (d. 403) supported MT 74% (41% against Alexandrian);

Chrysostom (d. 407) supported MT 88.5% (40.5% against Alexandrian); etc.

Whether these writers used the Egyptian text is not the issue here; indeed, perhaps Aland makes too much of this (and Pickering ably points this out). But to suppose that they used the Byzantine text as their primary texttype is demonstrably not true before A.D. 341. (Compare Asterius, above, with his predecessors.)

Third, Pickering argues that “any claim that Aland makes for the Egyptian text, on the basis of these Fathers, is a claim that can be made even more strongly for the Majority text” (p. 3). But this would only be true if the Fathers’ support of the majority text readings were support of distinctive majority text readings. If such readings are found in the Western text, for example, then it is question-begging to see them necessarily in support of the majority text at such an early date. In this connection it is significant that Hort argued that no distinctive Byzantine reading had been found in the Fathers in the first three centuries, a point that Fee echoed.

47 It is remarkable that majority text advocates acknowledge that Chrysostom did not use a full-blown Byzantine text—and even that Photius, a ninth-century writer, was apparently unaware of it. They use this argument against the idea of finding the roots of the Byzantine text in a particular official recension. Whatever are the merits of that argument, they should recognize that if Photius did not use the text in the ninth century, then it may not have been readily accessible even then. There is in fact some evidence that suggests that it was not until the ninth or tenth century that the Byzantine manuscripts really had high agreement with the Majority Text. More than one study has shown that the Byzantine text became more uniform and more like the Majority Text as time went on.

48 When it comes to Byzantine readings in the Fathers or in some of the papyri, the evidence will not bear the inference that the Byzantine texttype existed before the fourth century. Majority text advocates seem to confuse “reading” with “text.” Only by doing this can they make the claim that the majority text existed in the first three centuries. This can be seen by way of analogy. The King James Version is a “text,” as is the New American Standard Bible. But “In the beginning was the Word” is a “reading.” The fact that it is found in John 1:1 in both the KJV and the NASB does not imply that the NASB in toto existed in 1611. (In fact hundreds of phrases and even whole verses in the NASB are found in the KJV. All of these are isolated “readings.” Even with all these isolated readings that existed in 1611, it is not true that the NASB existed in 1611.) Yet this is the kind of inference that majority text advocates try to make out of isolated Byzantine readings that existed before the fourth century, almost all of which are found in other, demonstrably early texttypes.

49 Michael W. Holmes, “The ‘Majority Text Debate’: New Form of an Old Issue,” Themelios 8:2 (1983): 17.

50 Bruce M. Metzger, “Patristic Evidence and the Textual Criticism of the New Testament,” New Testament Studies 18 (1972): 379–400; idem, “Explicit References in the Works of Origen to Variant Readings in New Testament Manuscripts,” in Historical and Literary Studies, Pagan, Jewish, and Christian (Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1968), pp. 88–103; idem, “St. Jerome’s Explicit References to Variant Readings in Manuscripts of the New Testament,” in New Testament Studies: Philological, Versional, and Patristic, pp. 199–210.

51 Holmes, “The ‘Majority Text Debate’: New Form of an Old Issue,” p. 17.

52 Ibid.

53 Ibid. See, for example, Pickering: “The basic deficiency, both fundamental and serious, of any characterization based upon subjective criteria is that the result is only opinion; it is not objectively verifiable” (The Identity of the New Testament Text, p. 93).

54 See Holmes, “The ‘Majority Text Debate’: New Form of an Old Issue,” p. 17.

55 But this is not always true. In scores of places the editors of the modern critical texts have adopted a Byzantine reading against an Aleph-B alignment (contra Hort). This illustrates two things: (1) not only are internal criteria at times very objective—for the external evidence in such cases is often very much against the Byzantine reading—but it demonstrates the falsity of Pickering’s charge that modern textual critics “manipulate the text to [their] own subjective bias” (The Identity of the New Testament Text, p. 93); and (2) although the Byzantine text is not early, many Byzantine readings are—and these have the right to be heard when internal evidence is considered. As this writer has argued elsewhere, on the basis of internal criteria a number of Byzantine readings that have not found their way into the text of modern critical texts need to be given a hearing (cf. “Some Second Thoughts on the Majority Text,” and “A Textual Variant in 1 Thessalonians 1:10: ᾿Εκ τῆς ᾿Οργῆς vs. ᾿Απὸ τῆς ᾿Οργῆς,” Bibliotheca Sacra 588 [October–December 1990]: 470–79). It should be kept in mind that these Byzantine readings are almost never distinctive Byzantine readings.

56 That there are not many ‘A’ ratings (virtual certainty about the original) in the UBS text does not indicate overall uncertainty of reasoned eclectics about the text of the New Testament. Only 1,440 textual problems are listed, though there are over 300,000 textual variants among the manuscripts. The vast majority are not listed because the editors are quite certain about the true reading and/or such variants do not affect translation. Hence Pickering overstates his case when he points out that since there are five hundred changes between UBS2 and UBS3 even though the same committee of five editors prepared both, “it follows that so long as the textual materials are handled in this way we will never be sure about the precise wording of the Greek text” (The Identity of the New Testament Text, p. 18). Furthermore the charge could be reversed: Pickering and Hodges apparently disagree over 150 times on the wording of the text of Revelation (let alone the rest of the New Testament), for Hodges’s stemmatics led him to adopt a minority text more than 150 times for the Apocalypse.

57 It is certainly more objectively verifiable to count manuscripts than to deal with variants case by case. See, in particular, Pickering, “An Evaluation of the Contribution of John William Burgon to New Testament Textual Criticism,” pp. 86–91. In particular this comment should be noted: “A pronounced feature of the field of New Testament textual criticism today is the prevailing confusion and uncertainty…. It is high time that conservatives recognize both this fact and its implications” (ibid., p. 89). Furthermore this desire for (or insistence on) certainty is part and parcel of the inseparable link of inspiration to preservation that Pickering especially appeals to.

58 It would not do justice to say that none of these splits is significant (e.g., ἔχομεν/ἔχωμεν in Rom 5:1).

59 Aland, “The Text of the Church?” pp. 136–37, commenting on 2 Corinthians 1:6–7a. To be fair, Aland does not state whether there is no clear majority 52 times or whether the Byzantine manuscripts have a few defectors 52 times. Nevertheless his point is that an assumption as to what really constitutes a majority is based on faulty and partial evidence (e.g., von Soden’s apparatus), not on an actual examination of the majority of manuscripts. Until that is done, it is impossible to speak definitively about what the majority of manuscripts actually read.

60 The Identity of the New Testament Text, p. 150.

61 This quest for certainty often replaces a quest for truth. There is a subtle distinction between the two. Truth is objective reality; certainty is the level of subjective apprehension of something perceived to be true. But in the recognition that truth is objective reality, it is easy to confuse the fact of this reality with how one knows what it is. Frequently the most black-and-white, dogmatic method of arriving at truth is perceived to be truth itself. Too often people with deep religious convictions are certain about an untruth. For example cultists often hold to their positions quite dogmatically and with a fideistic fervor that shames evangelicals; first-year Greek students want to speak of the aorist tense as meaning “once-and-for-all” action; and almost everyone wants simple answers to the complex questions of life.

Related Topics: Textual Criticism